Tails of Ancient Rome

Humans and dogs have been partners for over 10,000 years

The inscription on the 2,000-year-old marble tombstone reads:

“Wet with tears I carry you, our little dog, as in happier circumstances I did fifteen years ago. So now, Patrice, you will no longer give me a thousand kisses, nor will you be able to lie affectionately around my neck. You were a good dog, and in sorrow I have placed you in a marble tomb, and I have united you forever to myself when I die. You easily matched a human with your clever ways; oh, what a pet we have lost! You, sweet Patrice, joined us at the table and asking for food from our lap, you were accustomed to lick the cup which my hands held for you and regularly to welcome your tired master with wagging tail ….” [1]

Another tomb inscription reads:

“How sweet and friendly she was! While she was alive she used to lie in my lap, always sharing sleep and bed. What a shame, Myia, that you have died! You would only bark if some rival took the liberty of lying beside your mistress. The depths of the grave now hold you and you know nothing about it. You cannot go wild with joy nor jump on me, and you do not bare your teeth at me with bites that do not hurt.”[2]

The ancient Romans loved their dogs. They imported them from all over Eurasia and North Africa and had dozens of breeds of dogs. They bred and trained them to be hunters, shepherds, watch dogs, fighters, and small lap dogs. Relatives of many of the breeds we know today, large and small, were known to the Romans.

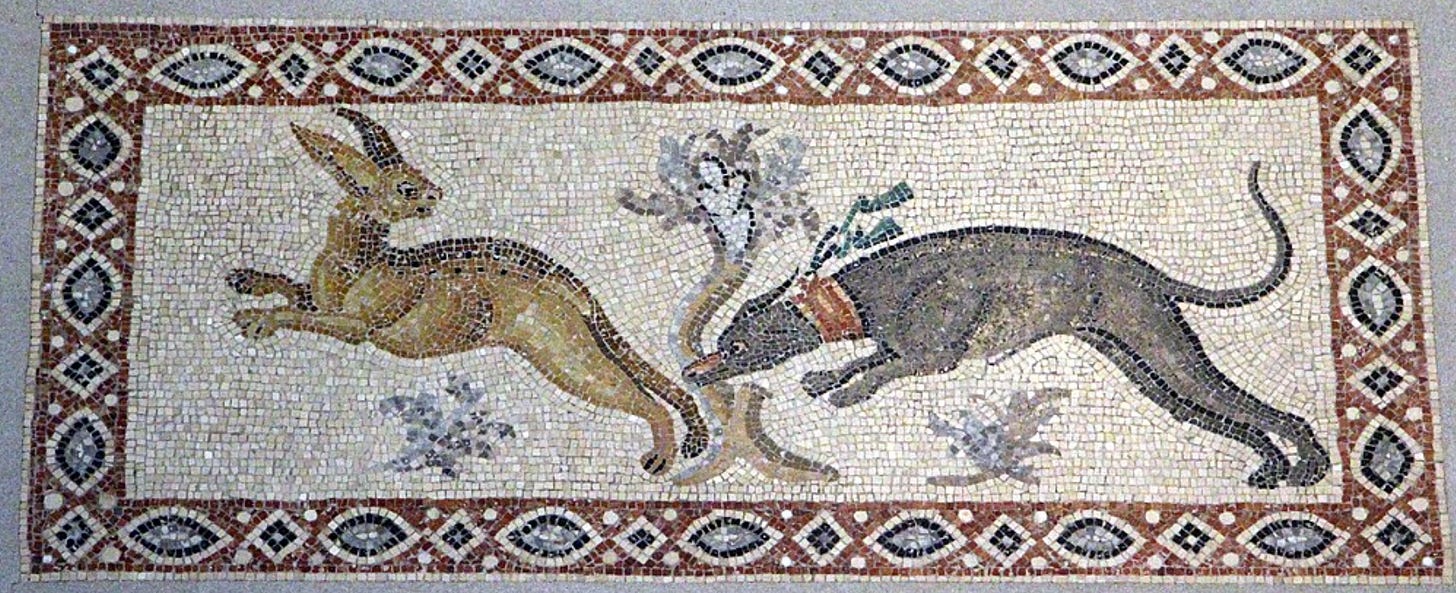

The Roman poet Grattius, writing in the last century BCE, provides a Roman geography lesson by listing the behavioral characteristics of dogs. “Dogs belong to a thousand lands and they each have characteristics derived from their origin”, he says and names many breed and their characteristics: dogs from Media in northern Iran, from the Celtic people of Scotland, and from Geloni (Ukraine), noting that they dislike fighting but are smart. He comments on Persian dogs and those come from Tibet and China, whom he felt were unmanageably aggressive. Lycaonian dogs (from Turkey) are big and easy-going; Hyrcanian dogs (from Georgia) are full of energy, and Umbrian dogs (from central Italy) are good trackers. Special praise was heaped on hunting dogs from Britannia (modern England and Wales), which were highly prized among Romans.[3] They were fast and tireless, chasing down prey. These were like Greyhounds, chosen for their speed and hunting instincts, and hunting dogs were often cited as important Roman imports from the British Isles.[4]

Many Greek and Roman authors wrote about breeding, raising, and training dogs for hunting. The Greek author Arrian (86 – c. 150 CE), writing during the early Roman Empire, wrote in a treatise on rabbit hunting, “If the dog has caught the hare or otherwise behaved well you should dismount and encourage him, and pat him, stroking his head, and putting back his ears, and calling him by his name, as, Well done, Cyrrah! Well done, Bonna! There's a good Orme! and so each by his name, for they love to be praised as well as men of a generous spirit.”[5] The Romans had many lap dogs, like little Patrice and Myia eulogized above. Small Melitaean dogs from Malta were a popular breed, but there were several sorts of dogs bred for small size and gentle dispositions. Some Roman writers remarked on just how smitten some of their owners were, allowing the dogs in bed with them, up on the furniture, and even sitting at meals. The satirical poet Juvenal (55-128 CE) quipped that he felt many wives would rather see their husbands killed than their dogs. According to Plutarch (46-119 CE), biographer of famous Greeks and Romans, Julius Caesar watched wealthy Roman women carrying their little dogs everywhere and asked if they had given up having children.[6]

The other favorite dogs of the Romans were the Molossians, bred for size, strength, and fighting ability. Their modern descendants are the mastiffs and pit bulls. These were the war dogs of both the Greeks and Romans. In Roman times they weighed up to 100 kg (220 lbs) and would go into battle fitted with armor and spiked collars.[7] Since ancient times dogs have been used in warfare, and they still are. In the U.S., 50-100 military dogs are trained each year by the Department of Defense Working Dogs Training Program in San Antonio. The dogs accompany patrols and detect hidden fighters and explosive devices. A Belgian Shepherd named Cairo accompanied Navy SEALS in the raid on Bin Laden’s compound.

All modern dogs are descended from Grey Wolves (Canis lupus), which had a wide distribution in Europe, Asia, and the Americas. The area where domestication first took place is still a matter of debate among geneticists and archaeologists, because early dogs are found in association with humans in early archaeological sites from Europe, the Middle East, East Asia, and Siberia. Based in part on the genetic differences between modern dogs and Grey Wolves, it is clear that the two started to diverge between 40,000 and 20,000 years ago. [8],[9] By the time for which researchers have ancient DNA extracted from dog bones in archaeological sites (around 10,000 years ago), a lot of genetic changes had already taken place in domesticated dogs, making their genomes clearly distinct from those of wild wolves.

All humans were hunter-gatherers during the late Pleistocene, hunting wild game and collecting many sorts of wild plants and animals for sustenance. Dogs and humans entered into a mutually beneficial relationship during that period, which continues to the present. Humans got the benefits of dogs’ spectacular sense of smell and their sharper hearing, as well as their speed, maneuverability, and strong jaws. Dogs got the assistance of humans’ larger brains and strategic ability to bring down larger game – horses, bison, and even mammoths and mastodons. In lands with saber-tooth tigers, lions, and other large predators, both dogs and people were safer camping together. Dogs also had an important ability, which is to pay close attention to what a person is seeing -- their “attentional state”.[10] This allows them to discern what the human is hunting for or trying to accomplish, and it feeds their desire to help if they can. (It also allows them to wait until you cannot see the hors d'oeuvres before they sneak one off of the coffee table.) The mutualistic relationship between humans and dogs has deepened over thousands of years, with dogs’ evolution shaped by human needs. In many cases this led dogs to evolve in many different directions, with differences between dogs bred for herding, sight hunting, scent hunting, pulling loads, guarding, guiding, being companions, and other functions. Humans have undergone genetic change as well, losing some of the acuity in their sense of smell and developing less robust jaws and dentition.[11] By the end of the ice age, the partnership was very strong.

In the last 10,000 years both species have undergone more changes. As humans came to rely more on domesticated starches such as rice, wheat, and corn, we have undergone natural selection that favored multiple copies of the AMY1 gene, which allows us to process starch more efficiently. (Chimpanzees have 2 copies of that gene but we have up to 20.)[12] Dogs underwent similar genetic changes in starch-processing ability at the same time, developing multiple copies of the gene AMY2B[13], and domestic dogs have as many as 30 copies while wild wolves have 2.[14] In a similar way, some humans evolved to have greater ability to process lactose from cow and goat milk, and many European dogs did as well, at just the same time.[15]

Recent research has shown that the genetic selection that gave rise to the different working breeds of dogs – hunters, pointers, herders, trackers, guard dogs, etc. – was going on long before Roman times. Research at the National Human Genome Research Institute has found correlations between behavioral and genomic characteristics of the working dog breeds, including marked differences in different breeds’ tendencies towards a range of characteristics including trainability, predatory chasing, aggression towards strange dogs and people, and ability to bond with people.[16] Anyone who has had both collies and children at a playground will have a sense of the dog’s herding nature, even if the dog has never seen a sheep.

By Roman times there were several relatively distinctive dog populations, in Europe, the Middle East, East Asia, Siberia, and the Americas. Dogs accompanied the first people into the Western hemisphere when they made their way there more than 12,000 years ago.[17] [18] [19] Almost all indigenous people of the Americas had dogs when they first encountered Europeans. Unfortunately, most of the genetic variability of these dogs was replaced by that of European dogs who came with European colonists. East Asia and the Middle East also became centers of dog genetic development and selective breeding in the last 10,000 years. The New Guinea “Singing Dogs” and Australian Dingoes are related to these early East Asian dogs. The Jindo dog, from Jindo Island in southwestern South Korea, also retains a lot of archaic East Asian dog ancestry.[20] Surprisingly, the history of the dog-human partnership is briefest in Africa. The first domesticated dogs are found in Africa only after about 5,000 years ago, and trace their ancestry to Europe and the Middle East rather than to wild Canids from African environments.[21] These domesticated dogs were quickly adopted by African hunters and herders, however, and were found all over Africa in historic times.

Humans and dogs share a special bond, and it shows up in all sorts of physical signs. When they are around each other, both dogs and people release oxytocin, a hormone that plays a role in a range of human behavior, such as love, social bonding, and parenting. Like all mammals, humans emit chemical signals about their emotional states – anxiety, contentment, sexual attraction, fear. These signaling hormones are released through tiny sebaceous and apocrine glands on our skin. For the most part, we are not conscious either of sending or receiving these signals, but it is clear that some people share a certain “chemistry”, quite literally. Dogs, with their powerful sense of smell, are even more consciously attuned to these chemical signals (so yes, dogs can “smell fear”). Using functional MRI observations, eye tracking, and behavioral preference tests, neuroscientists found that the interspecies bond works a lot like the bonding between a parent and child, with the brain (of both dogs and humans) responding much differently to perception of their own dog or human than to individuals who are only somewhat known or unknown.[22] Eye-tracking shows that dogs are intently focused on reading the emotional state of their caregiver, far more than that of other people in the room. This non-verbal signaling contributes to the sense that some dog-human teams seem to be able to communicate almost telepathically. The strength of this connection is felt by both human males and females, but it seems to be stronger among women, who report more positive feelings about their dogs. Being a caregiver for a dog has physiological consequences that are hard to discount: having a dog has been shown to reduce high blood pressure[23], decrease anxiety in difficult situations[24], and a large meta-study published by the American Heart Association in 2019 shows that dog ownership reduced humans’ all-cause mortality by 24%.[25]

Unfortunately, we sometimes hurt the ones we love, particularly when humans are in control of selective breeding. In the 19th century when “pure-bred” dogs came into fashion, concepts of “breed standards” came to cause dogs tremendous problems by leading breeders to select for sometimes arbitrary physical characteristics rather than behavioral strengths. In-breeding relating to producing these “desirable” traits caused congenital problems in dogs, such as the respiratory distress caused by flattened skull shapes of pugs and bulldogs, the spinal problems caused by the elongated bodies of dachshunds and corgis, the skin disease caused excessive skin folds of Shar Pei and Bulldogs, or the hip dysplasia caused by the sloping “angulated stance” considered desirable in German Shepards. Humans either introduced or exacerbated hundreds of these sorts of health-threatening traits through in-breeding, and unfortunately we are not yet out of the “pure-bred” era.

To watch a shepherd and a couple of Border Collies corralling a flock of sheep is to witness a virtuoso performance 10,000 years in the making. The dogs work in unison, flying around the herd, sprinting and then dropping flat to the ground, never breaking eye-contact with the sheep. The shepherd’s brief whistles and calls provide the little bits of coordination needed to move the sheep from one area to another, or into a pen. The dogs’ speed, agility, and instinct for herding allow them to do this work perfectly. Without dogs - the first domesticated animal - we could never have transformed the wild progenitors of sheep, goats, and cattle into the animals they are now, able to play the role they do in a pastoral economy. Other dogs are equally masterful at following scent trails imperceptible to humans, multiplying many times the hunter’s ability to bring back wild game. Without dogs, the hunter had just one chance to inflict a fatal injury upon the prey; with dogs, a hunter could wound an animal and track it, wound it again and track some more until the animal finally dropped from blood loss, exhaustion, or poison carried by the spear or arrowpoint.

Quite simply, were it not for the fortuitous partnership forged with dogs in the late Pleistocene, human history would not be the same. And dogs’ “best friend” status often comes with a strong bond of love. Anyone who has lost a beloved dog can identify with the Roman family that came up with this epigraph:

“I came from Gaul and my name, Margarita, comes from the sea. I learned to chase wild beasts boldly through the open wilderness. I never wore a collar nor felt the touch of a whip. I lie on the couches with my master and mistress’s family and can express myself more clearly than you might think any mute dog could. No dog’s bark could ever trouble me. Ah, but now I have met my end in childbirth and I rest beneath the earth, covered by this marble slab.”

Samuel M. Wilson is Professor Emeritus of Anthropology at the University of Texas, author of The Emperor’s Giraffe and Other Stories of Cultures in Contact, and a contributing editor to Natural History.

[1] Eagle Electronic Archive of Greek and Latin Epigraphy. Association Internationale d’Épigraphie Grecque et Latine – AIEGL http://www.edr-edr.it/edr_programmi/res_complex_comune.php

[2] https://thepetrifiedmuse.blog/2015/06/20/every-dog-has-his-day/

[3] E.S. Forster, "Dogs In Ancient Warfare," Greece & Rome 10 (1941) 114–117.

[4] Branigan, C. A. (2004) The reign of the greyhound a popular history of the oldest family of dogs / by Cynthia A. Branigan. 2nd ed. Hoboken, N.J: Howell Book House.

[5] Ancient Method of Coursing, from Arrian, Trans. Wm. Blane 1788, https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Cynegetica/Ancient_Method_of_Coursing,_from_Arrian

[6] Stewart, Aubrey (1894). "Life of Plutarch". In, Plutarch's Lives. Vol. 1. George Bell & Sons. Project Gutenberg.

[7] Roth, J. P. (2009) Roman Warfare / Jonathan P. Roth. Cambridge ; Cambridge University Press.

[8] Origins and genetic legacy of prehistoric dogs, Bergström et al., Science 370, 557–564 (2020)

[9] Thalmann, O. & Perri, A. R. (2018) ‘Paleogenomic Inferences of Dog Domestication’, in Paleogenomics. [Online]. Cham: Springer International Publishing. pp. 273–306.

[10] Call J, Bräuer J, Kaminski J, Tomasello M. Domestic dogs (Canis familiaris) are sensitive to the attentional state of humans. J Comp Psychol. 2003 Sep;117(3):257-63.

[11] Li B, Kamarck ML, Peng Q, Lim F-L, Keller A, Smeets MAM, et al. (2022) From musk to body odor: Decoding olfaction through genetic variation. PLoS Genet 18(2): e1009564.

[12] Carpenter, D., Mitchell, L.M. & Armour, J.A.L. Copy number variation of human AMY1 is a minor contributor to variation in salivary amylase expression and activity. Hum Genomics 11, 2 (2017).

[13] Axelsson E, Ratnakumar A, Arendt ML, Maqbool K, Webster MT, Perloski M, Liberg O, Arnemo JM, Hedhammar Å, Lindblad-Toh K. 2013. The genomic signature of dog domestication reveals adaptation to a starch-rich diet. Nature 495(7441):360-4.

[14] Arendt M, Fall T, Lindblad-Toh K, Axelsson E. Amylase activity is associated with AMY2B copy numbers in dog: implications for dog domestication, diet and diabetes. Anim Genet. 2014 Oct;45(5):716-22.

[15] Liu YH, Wang L, Zhang Z, Otecko NO, Khederzadeh S, Dai Y, Liang B, Wang GD, Zhang YP. 2021. Whole-genome sequencing reveals lactase persistence adaptation in European dogs. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2021 Nov;38(11):4884-90.

[16] Dutrow et al., 2022, “Domestic dog lineages reveal genetic drivers of behavioral diversification” Cell 185, 4737–4755

[17] 27 June 2022. "Peopling of the Americas". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

[18] Botigué, L., Song, S., Scheu, A. et al. 2017, Ancient European dog genomes reveal continuity since the Early Neolithic. Nature Communications 8, 16082

[19] Perri AR, Feuerborn TR, Frantz LAF, Larson G, Malhi RS, Meltzer DJ, Witt KE. Dog domestication and the dual dispersal of people and dogs into the Americas. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021 Feb 9;118(6):e2010083118.

[20] Bergström et al., Science 370, 557–564 (2020)

[21] Origins and genetic legacy of prehistoric dogs, Bergström et al., Science 370, 557–564 (2020)

[22] Karl S, Boch M, Zamansky A, van der Linden D, Wagner IC, Völter CJ, Lamm C, Huber L. Exploring the dog-human relationship by combining fMRI, eye-tracking and behavioural measures. Scientific Reports 2020 Dec 17;10(1):22273. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-79247-5.

[23] Allen, Karen; Shykoff, Barbara; Izzo, Joseph (2001). "Pet ownership, but not ace inhibitor therapy, blunts home blood pressure responses to mental stress". Hypertension. 38 (4): 815–820.

[24] Nagengast, S.L.; Baun, M.M.; Megel, M.; Leibowitz, J.M. (December 1997). "The effects of the presence of a companion animal on physiological arousal and behavioral distress in children during a physical examination". Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 12 (6): 323–330.

[25] Caroline K. Kramer, Sadia Mehmood and Renée S. Suen, 2019, “Dog Ownership and Survival: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis” Caroline K. Kramer, Sadia Mehmood and Renée S. Suen https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.119.005554Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes.